5 Important Reasons to Not Plant Ligustrum (Privet)

If there is one plant you should avoid at the nursery, it is Ligustrum (also known as Privet), an ornamental shrub. If you already have it growing in your yard, you may want to consider taking it out.

Why? Because Ligustrum is a highly invasive non-native plant that is taking over wooded areas throughout the Eastern United States, crowding out native species and drastically reducing biodiversity in those areas.

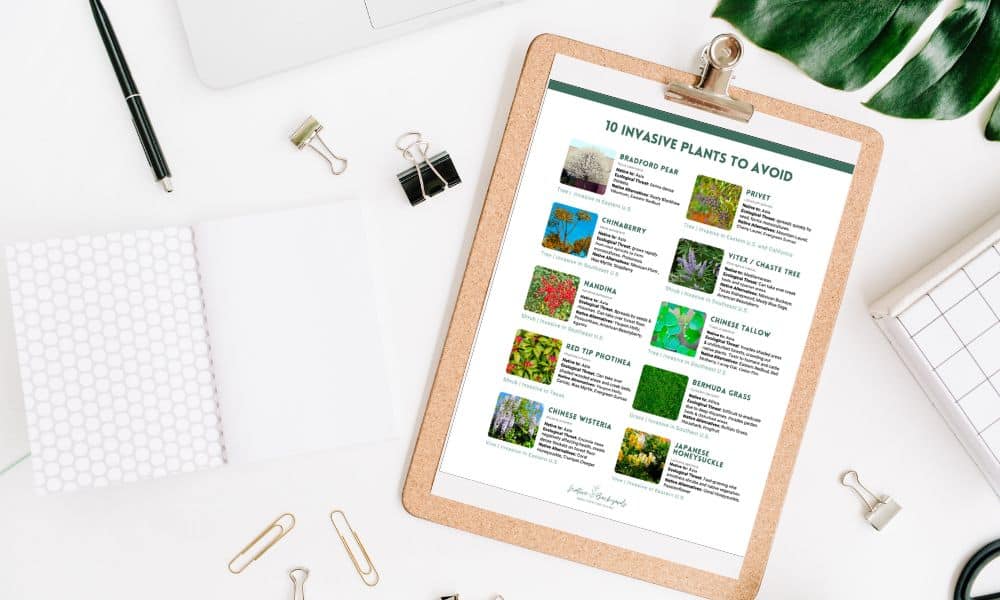

If you want to learn more about non-native invasive plants like Ligustrum, be sure to download my FREE 10 Invasive Plants to Avoid PDF!

Ligustrum is one of the most problematic invasive species we are dealing with today in the U.S. (just ask my Master Naturalist friends who have spent endless volunteer hours trying to remove it!).

However, it is still being readily sold at nurseries throughout the country with other invasive species like nandina. Let’s work together to stop this!

What is Ligustrum?

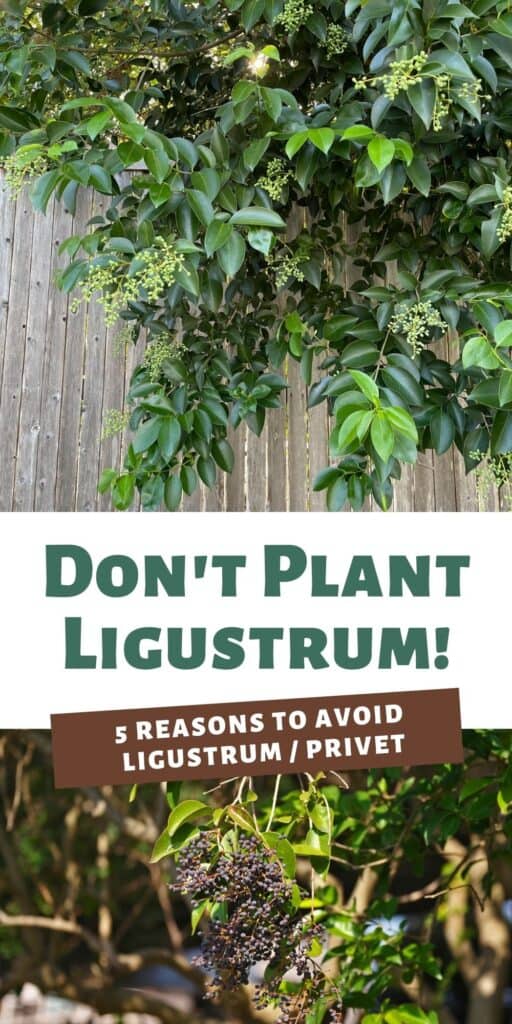

Ligustrum (Privet) is a semi-evergreen shrub / small tree with dark green leaves that can reach up to 50 feet high. It grows in full sun to partial shade and forms dense thickets, making it a popular landscaping shrub for hedges. Like other invasive plants, it grows in all soil types.

(Photo source: Canva.com)

Large clusters of white flowers cover ligustrum in late spring and early summer (between April and June). They are followed by dark purple to black fruit clusters (called drupes) from late fall through the winter. This is when the plants are most easily identifiable.

The fruit is also what makes this plant so problematic. Birds easily disperse the fruit seeds to areas outside of where it was planted.

5 Reasons to Avoid Ligustrum / Privet

If there is a swear word among the Master Naturalist community, it is “ligustrum”! Admittedly, I had never heard of the plant before becoming a Texas Master Naturalist in 2020.

It didn’t take long before I heard about its negative impact on natural areas only to discover I had some growing in my own yard. Here are reasons why it is so bad:

1. Ligustrum easily escapes cultivation when birds disperse its seeds

Ligustrum trees are easy to identify in the winter because they are teeming with clusters of black fruit.

While birds like Cedar Waxwings do eat the fruit, it is not worth the problems created by them dispersing the seeds.

2. The trees quickly take over forested areas, forming monocultures

Privet is an understory shrub (although some can get up to 50 ft. tall). Once established in a wooded area, it crowds out most of the native plants in the understory and quickly changes the ecology of the area.

3. When privet takes over, pollinators disappear

You won’t see many pollinators in ligustrum filled forests. A study by the US Forest Service showed the wildlife impact of removing ligustrum.

Two years after removing ligustrum from a forested area, they recorded 4-5 times more bee species, and 3 times as many butterfly species as areas still filled with ligustrum.

The good news: removing the ligustrum brings back the pollinators!

4. Once it spreads, it is hard to eradicate

Removing ligustrum that has spread through a large area requires diligence and ongoing monitoring for regrowth after the plants are removed.

Read on to see how the Headwaters Sanctuary, a local San Antonio nature preserve, is engaging in a multi-year effort to rid its 53 acres of ligustrum.

5. The less we buy it, the less nurseries will carry it

This is important. The more we become informed as consumers, the sooner garden centers will stop selling these plants. Please ask your local nursery to not carry ligustrum (send them this article!).

Download the Free Invasive Plants PDF

Want to learn about non-native plants that have become invasive in parts of the United States? Download this FREE PDF to start. It contains a photo and information on 10 problematic plants that are still being sold by nurseries.

These plants escape cultivation in our yards and spread to natural areas, often crowding out native species and forming monocultures.

Case Study: Ligustrum Removal at the Headwaters Sanctuary

I have seen firsthand the amount of work it takes to remove ligustrum that has invaded forested areas. Here in San Antonio, the 53 acre Headwaters Sanctuary is the largest nature preserve in the middle of the city. However it is flooded with ligustrum.

I recently interviewed the Headwaters’ Executive Director, Pamela Ball, to learn more about their ligustrum removal efforts.

Ligustrum escaped from surrounding neighborhoods

No one has ever deliberately planted privet at the Headwaters Sanctuary, yet its 53 acre wooded area is full of it. “For decades, homeowners in the surrounding neighborhoods have purchased Ligustrum as a hardy, evergreen hedge. We are inundated as a result.”, says Ball.

According to Ball, “Some zones are packed so heavily with ligustrum you can’t see the sky or hear birds. An ecologist told me she’s only ever seen one bird’s nest come out of ligustrum. You don’t hear birdsong in these parts of the sanctuary.”

The Headwaters created a multi-year plan to tackle infestation

Starting in the fall of 2019, the Headwaters started to do something about it in a big way. Ball divided the Sanctuary into 18 zones to help tackle privet removal and keep track of progress within each zone. So far, two zones are almost complete.

Each week a team of up to 20 volunteers from the community and local universities meets to cut down ligustrum, treat the stumps with herbicide, and put the branches through a wood chipper.

Teams of volunteers have removed 18,000 plants to date

Despite setbacks due to the pandemic and other hurdles, volunteers have steadily worked on two of the zones, removing upwards of 18,000 plants (80% of them ligustrum in various sizes).

“Some of the ligustrum plants we removed have multi-limbed trunks that can be two to three stories tall“, says Ball.

There is still a long way to go. Ball hopes to continue moving through all 18 zones, with a targeted completion date in 2025.

There are already signs of restoration of natives and wildlife

Ball recently assessed one of the zones where the ligustrum has been removed: “We have a pocket of Wafer Ash, Heritage Oaks, Hackberry, Condalia, Cedar Elm, Anaqua, and Hackberry in one of the zones we’ve cleared.”

“We have seen more bird activity as well. However, there is not a lot of understory yet because of the shade the ligustrum produced”, says Ball.

You can help the Headwaters initiative!

If you live in San Antonio, the Headwaters Sanctuary can always use more volunteers to help on Wednesdays and Saturdays with ligustrum removal. Email Pamela Ball at [email protected] for more information.

How to Remove a Ligustrum Tree

If you have privet growing in your property, here are the steps you can take to remove it:

1. If the plant is small, dig it out

The best thing you can do is get to the ligustrum seedlings before they grow larger. Dig them out, removing all the roots.

2. If the plant is large, cut it down to the ground

Larger plants may require a chainsaw to cut down.

2. Apply herbicide to stump

Removing privet typically requires a herbicide application. The Headwaters uses a heavy duty herbicide called Pathfinder 2 to spray the trunk and root collar. They combine the herbicide with dye so they can see it when spraying it.

3. Monitor for regrowth

Even with the herbicide there will be regrowth. Monitor every few months and hand prune and apply more herbicide as needed.

Types of Privet to Avoid

There are several different types of ligustrum species sold at nurseries, which should be avoided. These were all introduced to North America from other continents. All of them look fairly similar to each other but have different common names.

1. Ligustrum sinense (Chinese Privet)

According to the USDA, Chinese Privet (l. sinense) is one of the worst invasive species in the South. It thrives in the warm climate of the Southeast, and has completely taken over many of the wooded areas in that region.

Chinese Privet was introduced in the US from Asia in the 1800s and escaped cultivation by the 1930s, continuing to spread over the past nearly 100 years. According to Wildlife.org, it is the primary cause of biodiversity loss along streams in the Southeast.

2. Ligustrum vulgare (European Privet)

Native to Europe and Northern Africa, this species of privet (l. vulgare), also known as “Common Privet” is taking over forests of the Northeastern United States. It is listed in the Global Invasive Species Database.

3. Ligustrum japonicum (Japanese Privet)

L. japonicum looks similar to Chinese Privet, but with larger and thicker leaves. It also goes by the name “Wax Leaf Ligustrum” and is listed as a Federal and Texas Department of Agriculture noxious weed.

4. Ligustrum lucidum (Glossy Privet)

Glossy privet (l. lucidum) can grow up to 50 feet tall. It is considered invasive in states including California, Florida and North Carolina.

Are All Ligustrum Plants Bad?

The quick answer is, yes, most of them are! All of the privet species listed above are invasive in certain areas of the U.S. There is a sterile variety of ligustrum called Sunshine Ligustrum that do not produce fruit, and therefore can’t spread by seed. By why plant it when there are more beneficial native plants out there?

Native Alternatives to Privet

Evergreen shrubs that are native to the United States make great non-invasive alternatives to privet. Here in Texas great native alternatives to privet include:

- Cenizo

- Yaupon Holly

- Cherry Laurel

- Mountain Laurel

- Evergreen Sumac

- Wax Myrtle

- Dwarf Barbados Cherry

Pin this to help spread the word!

Welcome to Native Backyards! I’m Haeley from San Antonio, Texas, and I want to help you grow more native plants.

I have seen firsthand how the right plants can bring your yard to life with butterflies, bees, and birds. I’ve transformed my yard with Texas natives and I’m excited to share what I’ve learned with you.

Join my newsletter here! – each week I’ll send you helpful tips to make your native plant garden a reality!

Want to learn more about me and my garden? Check out my About page!

there a horribal plant there also bad for asthmatics and cause asmthma attacks as well as bad for people who suffer alliges and are poisness to people and animales too we have way to many in Tamworth new south wales Australia they clog up the sides of the river i have complained to the council and the people who work on the land they will do nothing about it

Virginia, I’m sorry to hear they are a big problem in Australia as well. That is such a bummer! I had heard about the pollen being bad as well. Keep up the good work raising the issue with your local council. Hopefully they will eventually learn.

I could not disagree more with your opinions. If separated out to 6 feet they create a beautiful forested area… with lots of positives.

I don’t disagree that the trees can be aesthetically pleasing, but the concern is that they can have a negative ecological impact when they escape cultivation and dominate forested areas, crowding out native species, and causing a reduction in biodiversity. Here is a link to a global review of Lugustrum Lucidum as one example: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12229-020-09228-w. The study found that forests invaded with Ligustrum “create low light conditions in the understory, hampering the establishment and growth of most species of trees, shrubs and climbing plants, ultimately resulting in the dominance of L. lucidum and the exclusion of native species”….”In general, monodominant L. lucidum forests has lower species richness, diversity and equitativity than native forests of similar ecosystems”

I do agree they are INVASIVE! I am in San Antonio as well and my home already had Ligustroms planted when I moved in. They were a great plant for screening & privacy but i am constantly pulling the plants that sprout from the berries they produce. They are a very messy tree and i want to get rid of them. I do not recommend planting ligustroms. I am totally natural and organic in my yard but I do not have any pollinators so I am curious to see if your claim is correct that these plants keep the pollinators away. I will continie my fight to eradicate this invasive shrub and hope for the return of bees, butterflies and dragonflies to my garden.

We are in Orlando and have a number of beautiful ligustrum in our yard. Over the past 52 years we have never had a seedling produced by them. When we bought the home, there were numerous large privets in the yard which we cut down and still get little seedlings popping up 30 years later. These privets looked a bit different from our Ligustrum and local arborists distinguish them

Rick Fletcher

How do they distinguish Chinese privet from Chinese privet

And the fruiting is eaten and spread everywhere when digested. So you may not see but the offspring of your bushes are all around you for dozens of miles and more.

Be careful…. Barbados cherry will take over an area, and is very hard to get rid of.

What are native hedge material for south Louisiana?

Richard – my apologies for the delayed response! Here is a helpful list of evergreen / semi-evergreen hedges that are native to Louisiana: https://www.lsuagcenter.com/portals/communications/news/news_archive/2012/march/news_you_can_use/native-shrubs-trees-are-worthwhile-additions

Our neighbors have these taking over their backyard. They get huge. When they re-seed the tape root is very long. You have to pull them out early or good luck getting the sprouts out. I have been vigilant in my yard, but unfortunately, our neighbors have not. They have taken over their entire yard! I was wondering what they were and just found this website. I am an avid gardener and have a very diverse bee/butterfly/bird habitat in my yard. I just wish our neighbors would do something about their overgrowth. Cedar waxwings are having a feast now on the berries, probably the only good thing about them.

In Houston I have always seen two plants called “ligustrum.” One called “wax leaf ligustrum” in local nurseries has very glossy leaves and does not develop the berry “drupes.” This “wax leaf ligustrum” as we call it in Houston doesn’t spread at all. For example, the now declining ancient wax leaf ligustrum hedge around the 3 mile perimeter of Rice University has not given birth to a single seedling in the sixty years I have been around it.

The other kind of ligustrum, not sold anywhere but growing everywhere like a weed, we tend to call “Japanese Ligustrum.” It is a true invasive plant, and is certainly much less ornamental with plain, dull dark green leaves and a rangy branching habit.

Can you shed some light on what sounds to like a problem of nomenclature?

Hi Hugh, thanks for your comment. Wax Leaf Ligustrum is typically the common name used for Ligustrum japonica (Japanese ligustrum). Here is some more information on it: http://www.tsusinvasives.org/home/database/ligustrum-japonicum. However, what you are describing without drupes sounds like a sterile variety similar to Sunshine Ligustrum (Ligustrum sinense ‘Sunshine’). Ligustrum is often spread outside the cultivated areas by birds consuming the drupes and depositing them elsewhere. If the Ligustrum you are describing doesn’t have drupes, it likely does not spread as easily. Next time you are at the nursery, take note of the Scientific (Latin) name and whether it has a name in quotation marks following the scientific name, which would indicate a cultivar like “Sunshine”.

Recently I had to research this species because my HOA planted this tree in my front yard when they removed a tree that was causing damage with the roots. Although listed on the list of trees the City accepts as a replacement, no one from the landscaping or HOA considered the poisonous aspect and the invasiveness of the tree. I contacted my local commissioner and stayed determined to remove this tree. As a grandmother of three kids under the age of two, and after reading the harm the seeds provide I made it my mission. I am thankful for your article as I will now move with a suggested for the city to remove this tree as a preferred tree to replace when removing permits are issued. I referenced the ornamental shrub to make sure this would never grow more than what was there blocking view to my front door and potentially being an area that someone could hide at night when coming home.

Much love and thanks for keeping us informed.

I’m curious, and totally ignorant on these . was going to purchase a bunch of them for a pasture . I have one near the house , bird feeder , and it’s grown well over 30′ . it’s covered in monarch butterflies when flowering , and honey bees . Thinking twice about it . Soil is farmed out clay and nothing grows in that area . Native pines is choice #2 .

Hi Dave, Thanks for your question. You are right that nonnative plants like Ligustrum can still offer some wildlife benefits – like nectar for pollinators. Birds like Cedar Waxwings will also feast on the berries (that is how they spread so readily!). I think the problem with certain invasive non-native plants is their tendency to spread rapidly beyond where they are grown and take over a natural area, crowding out existing native species and forming a monoculture of Ligustrum. Over time, that cuts down significantly in the biodiversity of that area. While honeybees and butterflies may still be attracted to the blooms in spring there are fewer species that the area supports when it is primarily a Ligustrum forest. A study by the US Forest Service showed the wildlife impact of removing ligustrum. Two years after removing ligustrum from a forested area, they recorded 4-5 times more bee species, and 3 times as many butterfly species as areas still filled with ligustrum.

For that reason, I highly encourage you to choose native trees for your pasture! If you let me know where you are located, I can help send you some ideas!

Hello,

I’m in North Carolina and am in the planning stages of planting 35′ of a tall screening bush/plant in an urban setting. Ligustrum’s are pretty, fast growing and fill a niche of many who are seeking screening. Waxleaf was on the top of my list until I started to research pictures which led me learn about their invasive nature. Can you offer a full ‘bush’ like, fast growing, non-deciduous, sun loving alternative that can create a screening from roadside traffic and peering neighbors? Please.

Hi Shelle, Thanks for you comment. I am not very familiar with North Carolina native plants (I’m located in Texas). However here are a few suggestions from the North Carolina Native Plant Society of native evergreen small trees and shrubs that you may want to look into: American Holly (small tree), Red Cedar (small tree), Rosebay Rhododendron (large shrub). Here is a link to all their North Carolina native plant recommendations: https://ncwildflower.org/recommended-native-species/